Jacqueline Wallace, of Phoenix, sat enjoying the December 1993 holidays at her son’s home in Gaithersburg, Md. But when she stood up and took a step, her holiday took a turn for the worse. Wallace fell and fractured her hip.

“My foot dragged a little, not exactly a stumble,” Wallace says. “I don’t know whether the bone broke because I fell, or I fell because the bone broke.”

Despite her 84 years and weak heart, Wallace had a lot going for her after her fall: modern medical practice and determination to walk again. Surgery to implant an artificial hip joint took under 45 minutes. (The x-ray at right shows the artificial left hip in sharp contrast with the bones of the normal right hip.) Spinal anesthesia and sedation were administered instead of general anesthesia because they are thought to pose less risk. And her physical therapy began the day after the operation.

“I fussed,” she says. “I was afraid it was going to hurt or I’d fall. But they said if you want to go home, you have to do this. And I did. It was more scary than painful.”

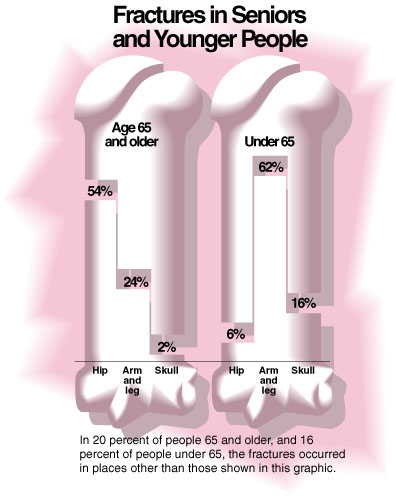

Wallace’s fracture was one of 1.5 million–including 336,000 hip fractures–reported in 1993, the latest year for which the National Center for Health Statistics has figures.

Besides surgical repair, treatments for broken bones include bone manipulation to reduce the fracture, use of a cast, and bone stimulation. Central to fracture healing is bone biology. Many treatments, some on the horizon, are designed to improve the natural course of healing.

Bones at Work

For skeletal growth and maintenance, the body’s 206 dynamic, living bones renew themselves lifelong through a continual breakdown, build-up process known as remodeling. This process is also involved in the remodeling of fractures, says Martin Yahiro, M.D., a Baltimore orthopedist in private practice and a consultant on fracture treatment devices to the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

In remodeling, complex chemical signals prompt cells called osteoclasts to break down and remove (resorb) old bone, and others called osteoblasts to deposit new bone. Many elements influence remodeling. Among them: weight-bearing, vitamin D, growth factors, prostaglandins, and various hormones, including estrogen, thyroid, parathyroid, and calcitonin.

As 80 percent of the mature skeleton, compact cortical bone supports the body, providing extra thickness mid-shaft in long bones to prevent their bending. Cancellous bone, whose porous structure with small cavities resembles a sponge, predominates in the pelvis and the 33 vertebrae from the neck to the tailbone. A fibrous membrane called the periosteum covers bone.

For healing and health, living bone must have a steady supply of nutrients. Blood vessels permeate bone to provide this lifeline. Blood-forming elements fill the long bone inner canals.

When a Bone Breaks

Fracture breaks continuity of bone and of important attached soft tissue–including blood vessels, which spill their contents into surrounding tissue.

Even before treatment, the body automatically seeks to repair the injury. Inflammatory cells rush to destroy, dilute or isolate invaders and injured tissue. Tiny new blood vessels called capillaries begin growing into the site. Cells proliferate. The injured person usually must endure pain, swelling, and increased heat at the breakage site for one to three days.

New tissue bonds the fractured bone ends with a soft callus, a mass of connective tissue and exudate (matter escaped through blood vessel walls). Remodeling begins. Within a few months, a hard callus replaces the soft one. Remodeling restores the inner canal.

Once restoration is complete, which may take years, the healed area is brand new, without a scar. Usually thicker, the new bone may even be stronger than the old, Yahiro says, adding that if the bone should break again, it’s unlikely to be at the same place.

And children’s bones have a healing boost: They’re growing.

“The growing skeleton is just geared to make bone,” Yahiro says. “A very young child’s wrist bones grow a millimeter a month, to rapidly correct misalignment or length defects. An adult may take six to eight weeks to heal a wrist fracture, a 5-year-old only three.”

When the ends of a fractured bone, such as an arm bone, form an abnormal angle, the doctor must decide whether to push the ends together (manipulation) to reduce the fracture, possibly under anesthesia. Simple x-rays aid evaluation.

“If it’s a large angle, we’d want to reduce that fracture,” Yahiro says. “But if it’s a small angle, especially in a young child whose growth will correct it, we’d probably just put the limb in a cast.”

The 95K JPEG graphic below illustrates common sites of bone fractures in seniors and younger people. Click on the image to enlarge it- and use the back button on your browser to return to this article. (Source: National Center for Health Statistics’ National Hospital Discharge Survey, 1992. Infographic by Sam Ward.)

Surgery for Joint Fractures

Joint fractures usually require surgery, Yahiro says. “We try to restore the joint to perfect, like putting a jigsaw puzzle back together.”

An artificial joint can be used to replace a fractured head of the long bone in the hip, like Wallace had, or in the shoulder.

Total hip joint replacements are mainly made of titanium or cobalt-chrome alloys or other metals. Each replacement has a stem that goes into the thigh bone inner canal, a ball for the head, and a plastic cup socket–the latter usually only used if the joint is badly arthritic. Yahiro often uses bipolar joints–a big ball atop a smaller one. All these joint replacements are approved by FDA.

Approved replacements for fractures in shoulder joints also consist of a ball and stem.

Andrew Bender, M.D., the orthopedist who implanted Wallace’s partial replacement, says this simple model has been in use 30 to 40 years. “It has different size balls, one size stem, so it’s not an exact fit. But it gives what we call a three-point fixation for some immediate tightness. The stem has holes for bone to grow through and across for more permanence.”

Bender pressed in Wallace’s device without cement, a snug fit. He cements only if the fit is very, very loose. “Modern day hip replacement without cement is relatively quick, both sides. She had only one side done and good bone, so it didn’t take long.”

If a replacement fails, it usually does so within 5 to 10 years. Simple models tend not to fail in the very old, Yahiro says. “A person in a chair or bed most of the time won’t put demands on the joint that, say, Bo Jackson does.” (Jackson had a hip replacement in 1992 due to a football injury.)

For higher demand, there are more precisely fitted models.

A robot that drills a more precise hole for the stem, to possibly keep the joint intact longer, is under investigation for use in cementless hip joint replacements. (See “Robots in the Operating Room,” July-August 1993 FDA Consumer.)

An external fixator–a pin-and-rod frame–can keep the joint from being compressed by other bones, to heal before a load, or stress, is put on it again. Pins are inserted on one side of the limb through the skin, muscle and bone, out the other side, and attached to the external rod, forming the frame.

About 30 percent of patients get infected at the pin site, so meticulous hygiene is crucial. “It’s a race,” says Kenneth McDermott, who reviews the devices for the Center for Devices and Radiological Health. “The pin goes through the skin, and infection can go right down the pin.”

Internal fixation devices pose less risk of infection. These metal plates, rods, wires, screws, nails, pins, staples, and anchors may sometimes be left in. A tiny pin may not be felt, but plates or screws may cause irritation or pain. The decision whether to remove the device in a second surgery is made on a case-by-case basis.

Surgery to remove a screw in the very old may be too risky. For a 20-year-old, benefits of a second surgery may outweigh risks. In the ankle, plates and screws are customarily removed. Yahiro says, “The bones are so superficial, the device often rubs on the shoe.”

McDermott gives another reason for removing a plate or screw: “It can take the load off the bone, causing the bone to resorb and weaken.”

Fixators and internal fixation devices are used also for some mid-bone fractures.

Grafts

The surgeon may graft bone to replace a missing segment that had to be surgically removed due to infection.

For a small segment, tissue can be taken from the patient’s own bone (autologous graft).

Cadaver bone (allograft) may be used, especially for a large segment. Though dead tissue, cadaver bone provides a scaffold for living bone to grow into and remodel the graft. For healing to occur–and sometimes it doesn’t–the body must put blood vessels into the graft to nurture the new living bone as it replaces the dead tissue. Healing takes longer than with an autologous graft.

Another option is a substitute bone graft, fashioned with help from nonhuman substances. FDA recently approved two such grafts:

- Pro Osteon Implant 500 Coralline Hydroxyapatite Bone Void Filler(1992)–Fills holes near the ends of long bones in adults. It derives from marine coral, whose spongy calcium structure resembles human cancellous bone.

- Collagraft Bone Graft Matrix(1993)–Treats long-bone fractures and other injury-caused areas of missing bone of 30 milliliters (1.8 cubic inches) or less. The product–consisting of purified cow collagen and a chemical, hydroxyapatite-tricalcium phosphate–is mixed with the patient’s marrow into a paste and put into the area of missing bone to encourage new bone growth. It’s not for use in certain patients, such as those with osteomyelitis (bone inflammation) at the fracture site, severe allergies, or allergy to cow collagen, and those being desensitized to meat products, as the treatment injections may contain cow collagen.

When these substitute grafts are placed next to healthy bone, the body remodels them in the same way it remodels human grafts. But according to Center for Devices and Radiological Health reviewer Nadine Rosile, “The substitute grafts aren’t strong enough for use without a fixation device to stabilize the fracture.”

A bone filler paste now under investigation, however, is as strong as bone within 12 hours, according to a report of a study of patients whose wrist fractures were injected with the paste. The report, in the March 24, 1995, issue of Science, stated that the paste stabilized the bone during healing and was eventually remodeled. The patients had greater grip strength at six months than historical controls (other patients in the past who had not been treated with the paste) had at two years, the report stated.

Also under investigation are injections of growth factor proteins, such as morphogenic protein and transforming growth factor-beta, found naturally in the body in very small amounts.

“The proteins turn on cells to produce bone,” Yahiro says. “Animal studies show growth with injections similar to that with autologous grafts.” The hope, he says, is that injected fractures, even with large areas of missing bone, will heal faster and be stronger, without grafts.

Healing Helpers

FDA has approved seven electrical bone growth stimulators, mainly for fractures at the middle of long bones, such as the shinbone (tibia), that have not healed over at least nine months. Although exactly how the stimulators heal is unknown, manufacturers’ studies showed the devices did in fact affect cellular processes.

Yahiro explains that loading (stressing) a bone produces in it a small electrical field called piezo electric force, believed to stimulate new bone formation. “It’s believed that electrical stimulation does something like that on a large scale,” he says.

For direct stimulation, an electrode is implanted at the fracture, linked through the skin to a generator. For indirect stimulation, electric coils outside the limb on the non-fracture side induce an electrical field at the fracture side.

In 1994, FDA approved the first ultrasound bone growth stimulator. The Sonic Accelerated Fracture Healing System (SAFHS) is for adults with small fractures in the lower leg or lower forearm. A cast or splint is used. It is the first stimulator for the treatment of fractures occurring within seven days before treatment. Studies suggest that mechanical forces of the ultrasound waves transform into electrical impulses as they travel through the tissues.

The SAFHS consists of a portable generator cabled to a small, square treatment module that emits ultrasound pulses at about the same low intensity as sonogram fetal monitors. In some instances, the patient may use the unit at home. Recommended treatment is 20 minutes once a day until the fracture heals.

The SAFHS is not for patients who need additional fixation or surgery, are pregnant or breast-feeding, have bone disease or circulatory problems, or take medicines that may adversely affect remodeling.

In studies, all treated patients–and especially older people–healed faster than those using a placebo. In those age 50 and older, arms healed 40 days faster, and legs 85 days faster. Six years’ follow-up did not suggest long-term adverse effects.

Stimulation, grafts, manipulation, joint replacements, casts. Whatever the treatment, fracture healing is monitored by x-rays and physical examination to answer such questions as: Does it hurt or move when pushed on? On x-ray, does the fracture look healed? On x-ray, are the bones aligned?

For Wallace, healing is now complete. She is indeed walking again, using a cane as she did before the replacement surgery.

“If I don’t use the cane, my leg aches,” she says. “I’m still careful to use my good leg stepping up a curb, and my bad leg stepping down, like I learned in therapy.”

Dixie Farley is a staff writer for FDA Consumer.

Boning Up

The most important influences on fracture healing are nutrition and overall health, including bone health, before the injury, says orthopedist Martin Yahiro, M.D., a consultant to FDA. “That’s why it’s so important all your life to do weight-bearing exercise such as walking and get enough calcium and vitamin D, so you lay down as much bone as possible during growth and keep as much as you can later on.”

The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for calcium is 1,200 milligrams a day for people ages 11 to 24 and for pregnant or breast-feeding women. For men and women older than 25 who no longer have to meet the greater demands of growth, the calcium RDA is 800 milligrams a day.

In general, genes decide bone shape and size. But mechanical stress by muscle, body weight, and physical activity influence bone shape and density–and health–throughout life.

Simply put, loaded (stressed) bone strengthens, and unloaded bone weakens. As examples, astronauts’ bones weaken in outer space with no gravity pull on them, and the shaft of the humerus (long upper arm bone) in a professional tennis player’s dominant arm gets denser and thicker from the extra load.

The body increases its bone mass until, usually, the mid-30s, after which a gradual loss begins.

Age-related bone loss can lead to osteoporosis, a condition of thin, weakened bone that fractures easily. The condition affects many postmenopausal women, because bone loss increases with menopause due to lower estrogen levels.

In announcing its recent approval of Fosamax and Miacalcin Nasal Spray for osteoporosis, FDA advised that patients also exercise and get adequate calcium and vitamin D. Drugs approved by FDA to prevent or treat osteoporosis are:

- estrogen–Premarin, Ogen, and Estrace tablets; Estraderm patch

- estrogen packaged with progestin hormone tablets–Prempro; Premphase

- alendronate–Fosamax

- calcitonin–Miacalcin Nasal Spray, Calcimar Injection, Miacalcin Injection, and Cibacalcin for injection.

–D.F.